Recent Updates

12/23/2025 12:00 PM

Good gravy! Hunting Scotland's best festive food in the epic M3

12/23/2025 12:00 PM

Renault concept goes 626 miles on a charge at motorway speed

12/23/2025 12:00 PM

The road to self-driving cars that think and behave like humans

12/23/2025 12:00 PM

Driving the 330bhp, £375,000 carbon-bodied Elise

12/23/2025 12:00 PM

Top 10: World’s longest road tunnels

12/23/2025 12:00 PM

The Lotus Emira is a thrill if you've got the skill

12/22/2025 12:00 PM

How a cigar-chomping watchmaker invented the Smart car

12/22/2025 12:00 PM

The Christmas lunch bunch: Festive showdown in 2025's best cars

12/22/2025 12:00 PM

The McLaren Artura came of age in 2025 - now it's a true supercar

12/22/2025 12:00 PM

4000 miles in a Golf GTE: The company car for the helmsman

EV, Hybrid, Hydrogen, Solar & more 21st century mobility!

HPE's super-lightweight, Honda-powered R500 is a single-seater in drag

HPE's super-lightweight, Honda-powered R500 is a single-seater in drag

“I want to say the R500 is not a scary car to drive,†says Dan Webster, the earnestness in his Brummie tone entirely betrayed by the glint in his eyes. “But it probably will be scary the first time you drive it.â€

The deadpan delivery makes me laugh out loud, then quietly look inward. I get that Webster, who races an Elise and is the master engine tuner turned overhaul specialist behind Bromsgrove-based High Performance Engineering, rates his product. I also get that, with a McLaren F1’s power-to-weight ratio and a wheelbase shorter than that of a VW Up, the heartbreakingly expensive R500 is going to have some mischief about it. But genuinely scared? By a little Elise? Be serious.Â

What I’m about to discover is that the 330bhp HPE ‘Special Vehicles R500’, with its polycarbonate windows and plumbed-in fire extinguisher, is an S1 Elise in only the loosest sense. True, it stops short of being a silhouette racer, but only just. The familiar body is really just a doe-eyed Trojan horse for hardware and a degree of obsessiveness more common to motorsport. Beyond the donor car’s extruded-aluminium monocoque, which is stripped then replated, 80% of it is bespoke.

Bespoke and hardcore. You’ll find bladed anti-roll bars (notice how a plastic ruler’s vertical rigidity changes as you rotate it from flat to upright) that alone can transform the handling. There are also carbon-carbon brakes, and a power-distribution module that replaces the original Elise’s rat’s nest of fuses and relays. This PDM allows for on-the-fly brake-bias adjustment and motorsport traction control, while safeguarding an engine hooked up to more sensors than a SpaceX Falcon 9.

The rose-jointed suspension is also completely new, and the brake system is re-engineered to retain the original and sculptural pedal box but add dual master cylinders and a racing-style integral bias bar.

As for Webster (pictured below), the former prison architect is a Burt Munro-type character. Only instead of attempting to set speed records with an Indian Scout, he’s selling rampant synaptic overload and diamond-edged driving pleasure for people who know what they’re doing in a trackday car.

The motorcycle link is apt. It was in 1994 that Julian Thomson and Richard Rackham set out to create not so much a sports car but a four-wheel version of their Ducatis. At 640kg the R500 weighs fully one Joe Marler less than even the flyweight S1 Elise those men brought to life. Its engine, built from the bones of a Honda K20 unit, also spins to 10,000rpm, and is loud enough to warrant an intercom and a cache of ear plugs in the tray where the roll-cage passes through a carbonfibre sill. It’s fair to say that tin-tops with road-legal status and self-cancelling indicators don’t get any more ‘superbike’ than this.

Despite the wild premise, the R500 is still a bit of a sleeper, especially in the dull light of our garage at M Sport’s Dovenby Hall facility. That light gives the voluptuous surfaces a rather nondescript, development-mule appearance. It’s only when the car is effortlessly wheeled into the sunshine that the magnificent carbonfibre body, baked by Innovate Composites in Treorchy and with clamshells that weigh five kilos apiece, becomes obvious.

Sitting 60mm closer to the road than a standard S1, on Nitron coilovers with custom valving – and with a brutal diffuser exploding from beneath the open-worked rear bumper, through which the four-into-one titanium exhaust is visible – the R500 has something of the Elise GT1 about it.

It really does look very exotic – whether it’s £375,000 exotic is another question – but we should remember that modified Elises are famously easy to cock up when it comes to dynamics. On this occasion I have reason to believe that is unlikely. When Webster and I crossed paths at Anglesey in the autumn, and set today’s events in motion, he took me for some passenger laps. Talented drivers often make recalcitrant cars look surprisingly natural but the R500 seemed to reside within the narrow threshold between grip and slip purely out of choice; it was fierce but absolutely, thrillingly obedient.Â

My turn is now fast approaching. But first Webster finishes off what has been a Reith Lecture-worthy walkaround by explaining how 3D-printed engine mounts allow him to get a three-degree tilt on the mounts for the straight-cut dog ’box. This has better aligned the driveshafts without moving the engine, preventing the CV joints from overheating – a common K-series problem. This is just one of, oh, eight or ten examples of such intense, microscopic optimisation of the product.Â

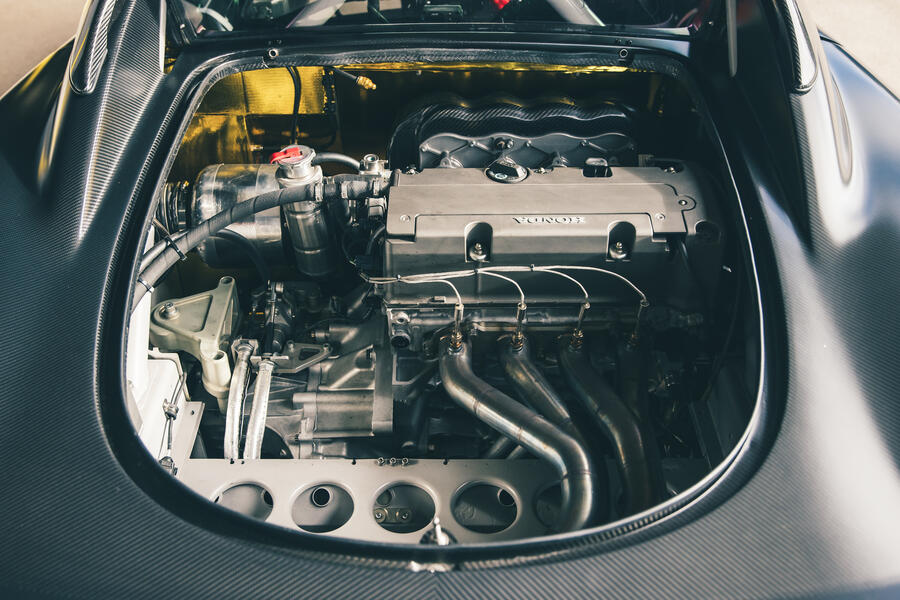

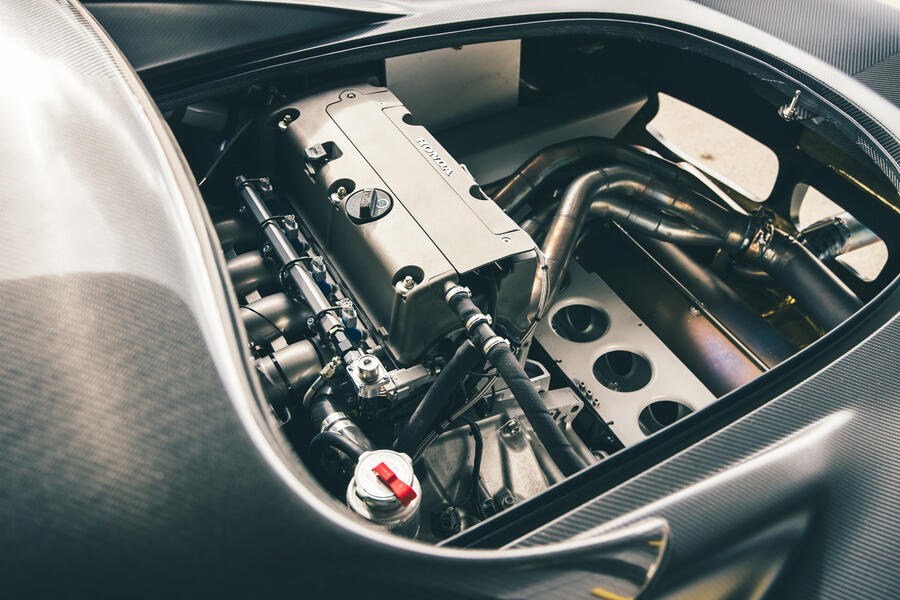

Nestled in its neat bay, the K20 itself is bored to 2.2 litres, runs at 13:1 compression and has a custom lightweight steel crank, forged con-rods and pistons, individual throttle bodies plus “huge valves and really, really hot camsâ€. How hot? More than 15mm of valve lift is about what you’ll find on a V10 F1 engine.

Having the top end in effect permanently on high-cam sounds promisingly lurid but doesn’t bode well for low-speed drivability. However, Webster insists the car will take wide-open throttle at 1500pm in sixth (spoiler: it does). He then produces an actual flywheel, seemingly from his pocket. It’s barely larger than a Wagon Wheel and at 1100g weighs about a third what the standard part does. Engine, plus flywheel, plus twin-plate clutch comes in at 83kg, versus 105kg stock. The valvetrain is so light the engine could theoretically spin to nearly 11,000rpm.Â

Folding yourself into the R500 generates a few more groans than the standard car on account of the T45 steel roll-cage. The door aperture is now hellishly tight but once ensconced and strapped into the Tilletts, you get that unmistakable, addictive, primitive thrill: rather than being bolted into the car, the car is more an extension of yourself. I don’t ride motorbikes but they’re surely the benchmark for this sensation. The R500 can’t be too far behind, just as Thomson and Rackham intended.

You then sit there drinking in the filigree billet-aluminium gearshift mech. Next is to prime the ignition via the smart bank of controls on the dash; turn to the TFT display on its beautifully machined plinth; and finally you breathe life into the engine with a prod of a button on the Momo steering wheel, which could be borrowed from Lotus’s 1994 F1 car.Â

The moment the K20 catches is the moment the R500 stops being in any way a cute S1 Elise. People talk about the powertrain feeling ‘present’ in 911 GT3s with a single-mass flywheel, but the fizzing energy of the R500 is off the chart by comparison.

Get going and the biting point is vindictively fine but this will be the last time you use the clutch. Upshifts require only a half-lift of the throttle as you navigate the H-pattern ’box, and on the way down the idea is to left-foot brake and blip the throttle with your right foot. It sounds dreamily simple, though my muscle memory is so damned stubborn when it comes to H-pattern shifts that today I’ll use a good old-fashioned heel-and-toe downshift. It’s slower – considerably slower – but without question a nice option to have and means I can focus elsewhere.

For the first few laps, ‘focus’ is the word. The brakes need lots of temperature, and this means riding them for a while. Meanwhile, the plated LSD in this car (customers will have the option of a more emollient Quaife unit) is also so tightly wound that, until you have heat in the tyres and commitment in your bones, it ploughs the nose wide constantly.

Clearly this car has a window, and right now I’m not in it. It is also easy to lock the brakes, though because the R500 is so light and its tyres are so narrow, there’s no screeching. The front axle merely goes light and the white smoke pours over the edges of the windscreen, some of it escaping through the wheel arch and into the cabin. It’s all very racing car. Â

But to the real question: is it actually scary? Yes. Though only in so far as you don’t want to blow such an incredible engine to smithereens with an errant shift. Given the stratospheric rev ceiling, you’d really need to get things horribly wrong, and K20s, even ones this finely honed, are tough cookies. But still, this waspish 2.2 feels so blueprinted, so special and so ridiculously ‘motorsport’ that you start out treating it with kid gloves. Which is perverse, because what this driveline wants is a proper beasting. Â

You need to be ready to administer exactly that. With cars as single-minded as the R500 there’s always a ‘clicking’ point. This is when operation ceases being a series of physical prompts and starts feeling more instinctive and ethereal, like flying. Problem is, it often exists beyond the level of commitment you tell yourself you’re prepared to go to when it's somebody else’s car. Especially if it’s chassis #001 and, on an emotional level, priceless.Â

In the case of the R500 – a machine that doesn’t rely on downforce – the clicking point is very high indeed. I can imagine plenty of people going to nine-tenths and, hyper-stimulated but a bit unmoved, thinking they’ll call it a day. And this would be a travesty. Only when you start driving the R500 like it’s the last thing you’ll ever do, does the mad thought that it might somehow be worth the outlay enter your mind. Wine tragics who’ve dropped a mortgage payment on a bottle of ’82 Latour and had their boundaries redefined will know the feeling. This Lotus can do that.Â

It starts with the engine. The lack of inertia manifests in its absurdly cutthroat responsiveness, of course, but the smoothness and speed of a well-executed 9500rpm upshift is what stays with you long after the drive has ended.

For my money the light action itself could have a touch more steeliness to it – not weight, note, but a hardness. Even so, here you have the gratifying violence and theatre of a sequential ’box with the sense of artisanal engagement of an H-pattern Group 5 historic. And the noise in those seconds before each shift. Jesus. Earlier, Webster said he always just wanted to drive cars that sounded like touring cars. That would explain the R500’s delicious carbon airbox, nestled against the gold-lined bulkhead.

By the time you’re familiar with this powertrain you’ll be going extremely fast. Can’t be helped. Red-line upshifts are a drug; full throttle the only permissible approach when 205lb ft of peak torque arrives at 8600rpm. It is also psychotically loud in here and so rapidly does the R500 gain speed that you’ll be busy – an upshift buys you about 20mph, which flat out takes the car only a second or so to dispatch. The point of sensory overload, in the best possible sense, often feels close at hand.Â

At this point I’d love to say something insightful about the handling but ultimately it is everything you need it to be. In the interests of keeping the car whole, today the chassis is softer at the back than Webster would usually have it and about 75% of maximum stiffness at the front. It is still no trouble at all to steer the supple R500 on the throttle, increments of yaw blithely taken here and there. I imagined the balance of power and traction might be awkwardly skewed but it isn’t.

While this car isn't exactly benign and I can imagine it getting away from you fast on a damp track, I can safely throw it around a bit, confident in its fundamental balance and the responses of the delicate, frothing, precise driving controls. It’s a grown-up Tony Kart: unfettered joy, and quite different to the Analogue Automotive Supersport, being more intense and grainy but perhaps less effusive. The driving experience of the hyper-specialised R500 is, it goes without saying, unique. Â

HPE plans to offer ‘lesser’ versions of this car in the form of the road-leaning R400 and R300, which will variously go without the carbon body, the roll-cage, the dog ’box and the three-way adjustable dampers. None will be remotely affordable and those considering an R500 – for which the build time is a year – will need to get comfortable with the opportunity cost (assuming such things concern them in the first place). That cost extends to, for example, a brand-new Manthey-tuned 911 GT3 RS. Or if the street-legal element isn’t important, half a grid of Radical SR1s.

It is huge money, of course. Scary money, you might say. But that aside, on a day like today, the R500 is a stunning bit of kit: a tiny prototype racer, tens of thousands of hours in the making, and one man’s Elise-based tribute to obsessiveness and raw thrills. Â

HPE Special Vehicles R500

Price £375,000 Engine 4 cyls in line, 2200cc, petrol Power 330bhp at 9000rpm Torque 205lb ft at 8600rpm Gearbox 6-spd manual Kerb weight 620kg 0-60mph 3.0sec (est) Top speed 165mph